Like you, I grew up hearing the story of Columbus and his “discovery” of “America.” We now know there was no “discovery” since this land was already inhabited for thousands of years before he arrived. He and his crew didn’t “discover” so much as they were lost when his ship crashed aground off the coast of the island of Kiskeya.

As Columbus’s ship was sinking, his own men in the accompanying vessels stood by and did nothing. The Taíno, the indigenous inhabitants of this island, however, didn’t hesitate. From shore, they witnessed a group of people in distress and paddled out in their canoes to save Columbus and his men.

First contact.

My ancestors treated them as guests and weary travelers.

By Columbus’ own account and according to subsequent settler-colonizers who documented their interactions with the original peoples of this land, Taíno were known for their extraordinary kindness. In his first missive to Queen Isabela I of Castile, sponsor and financial backer of this expedition, Columbus wrote: “The Taíno were the kindest, most gentle people I had ever met…”

This kindness wasn’t naivety. It was strength rooted in care.

Yet Columbus mistook their care for weakness. He continued in his communication to the queen: “A few men with swords could make slaves of them all.”

This pattern of exploiting human kindness would shape centuries of colonization to come.

I’m today years old still unpacking for myself the true story of first contact and its impact on me, my ancestors, and the world.

Which is what brings me to today as I write my own letter to you from Kiskeya, the island you know by its colonizer name: Hispaniola.

Because I’m a self-identified history nerd, I’ve gone down a few rabbit holes, piecing together what happened on and after Christmas Day, 1492. Yes, by many accounts #firstcontact happened on December 25.* (If you’re interested in a well-researched telling of this history, check out this video of Professor Roy Casagranda.)

After building the first European fort in the Americas called La Navidad (the irony of this name is not lost on me) with the remains of his busted ship, Columbus left that outpost to resupply men and munitions in Spain. Making good on his intention, Columbus returned to Ayiti in December 1493 with 17 ships and more than 1,000 men. Taíno resisting exploitation, led by kasike Caonabo, destroyed the original settlement on the northeast coast. (My ancestors were both kind and didn’t suffer fools.)

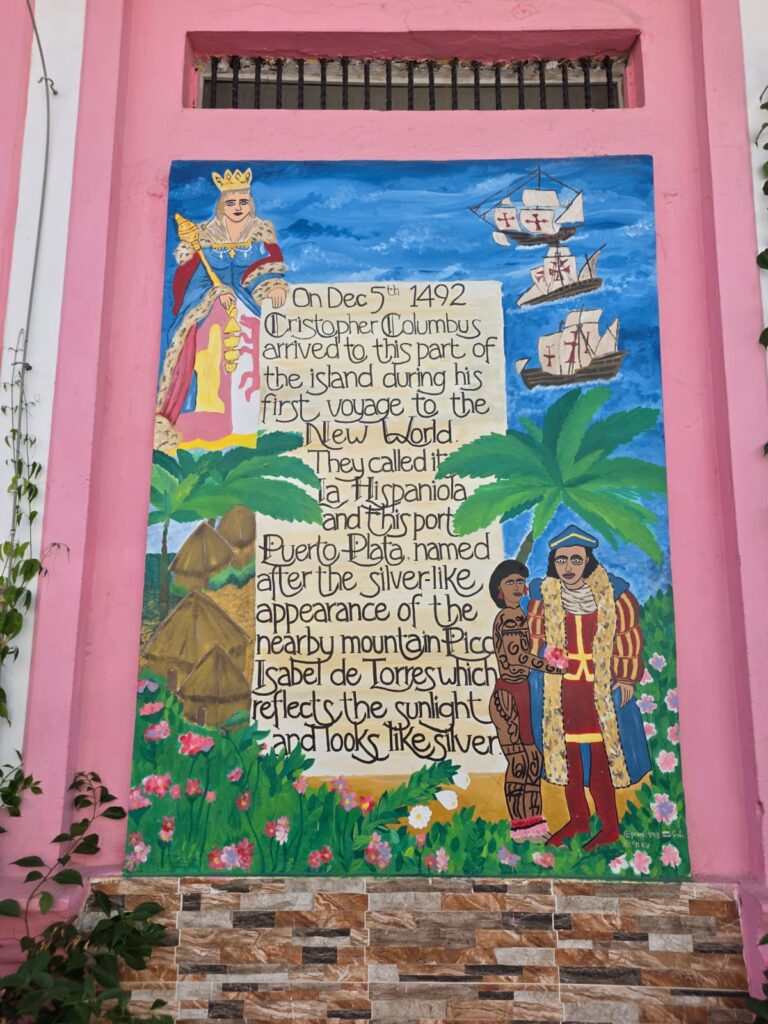

The history of first contact is told in murals on walls in Puerto Plata, Dominican Republic.

Columbus and his men killed or captured many Taíno, including Caonabo. It was on this second voyage that Columbus established the first permanent European settlement in the Americas: La Isabela, named for the queen herself.

This is where I will go this week.

As I walk the grounds of La Isabela, I will listen for what the land wants to tell me. I’ll be in conversation with these truths—not as distant “history,” but as living context for my life and leadership today.

My father embodied his Taíno heritage. For years, I mistook his gentleness and care for weakness, the same way Columbus had done with my indigenous ancestors.

Because my papi was the one who stayed home, cooked our meals, cared for me and my sisters—labor traditionally assigned to women—I thought he wasn’t strong. While it’s true my mother provided financial stability and navigated institutions with confidence, my father’s strength was in his kindness.

Our society conditions us to view leadership as dominance, power, and control. We’re taught that success means financial compensation, unwavering resolve, and visibility. Power becomes something we perform at the expense of others—not something we share or recognize as belonging to everyone. This narrow view costs us dearly, particularly women leaders who face countless double binds. These #nonchoices trap us: striving to “do it all” while always falling short; balancing career ambitions with endless family responsibilities; choosing between being liked or being seen as competent—but never both, at least not if you’re female.

There is another way.

The path forward isn’t about caring less. It’s about recognizing that caring itself is what it means to be human. It’s our superpower. When we lead with authentic care, we create the foundation for genuine transformation and lasting change.

This is a wisdom all humans know (I don’t think it’s unique to indigenous people). My Taíno ancestors put that knowing into practice. I witnessed it in how my father led and lived. And I believe it’s the leadership we urgently need today.

*The date of First Contact is disputed between December 5 and December 25, 1492.

Get to Know the Taíno

Taíno Terms

🗻 Ayiti / Haití: Indigenous name for the mountainous western part of Hispaniola; often extended to the whole island in contemporary usage.

🏡 Bohío: Traditional Taíno house or dwelling; another name given to the island that is now Haiti and Dominican Republic.

💙 Borikén: Indigenous name for Puerto Rico, homeland of many Taíno ancestors.

🌀 Hurakán: Taíno term for powerful tropical storms; root of the English word “hurricane.”

💪🏾 Kasike: Hereditary leader or chief of a yucayeke (village) or region; derived from the Taíno word kassiquan, which means “to keep house”.

🌎 Kiskeya: Another indigenous name given to the island now known as Hispaniola; meaning “mother of all lands” or “mother of the Earth”.

🌱 Kubao/Cobao: The name is widely accepted to come from the Taíno language for the island known as Cuba; likely meaning “where fertile land is abundant” or “great place”.

🌅 Tai’gúey: A greeting meaning “good day” or “good sun”.

💜 Taíno: Name given to Indigenous Arawakan peoples of the Caribbean; often glossed from “tai” (good) + “no” (people).

🌊 Xaymaca: The most commonly cited indigenous name for the island known as Jamaica, meaning “land of wood and water” or “land of springs” in the Taíno language.

🏘️ Yucayeke: Village or community settlement.